At this point, the majority of my friends who make or are otherwise involved with art have seen HBO’s new documentary about the corruptions at the top end of the roaring contemporary art market. The title itself says a lot about the content of this film. The Price of Everything is a truncation of a quote from Oscar Wilde, who had one of the characters in a play state that a cynic is a man who “. . . knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.” The creators of this exposé made a dutiful, if feeble attempt to raise the subject of the second half of that sentence in the person of the aged former art world insider — later turned outsider, and now re-surfacing prodigal — Larry Poons. But the crotchety old Poons, in his paint spattered pants and Bowery drunk’s knit turban, isn’t enough of, or as thoughtfully examined an example to override the filmmakers’ clear fascination with the spectacle of wealth that they lay before us. The triumph at the end of the story is Poons’ portended re-embrace by the very sharks whose existence we have been told throughout that his whole being contradicts. What exactly is that meant to tell us?

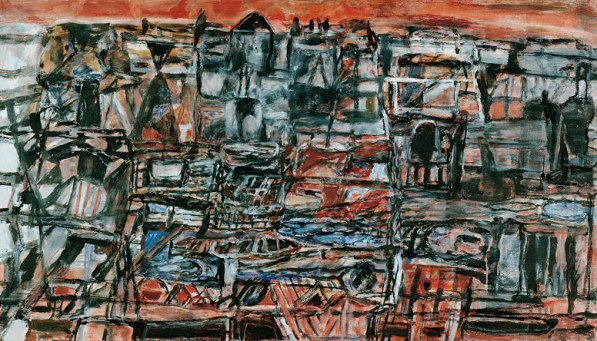

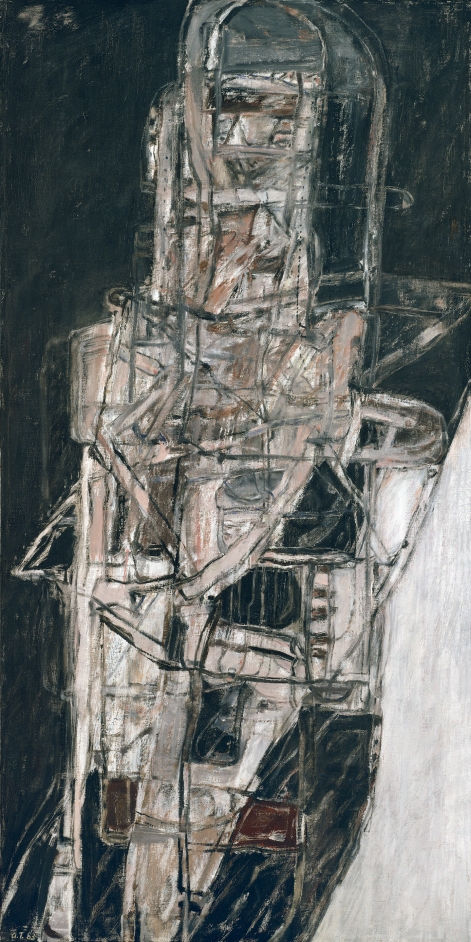

Making things by hand and eye, whether they be pictures — painted, mechanical or digital — sculptures in three dimensions, or all the different kinds of handmade things that have traditionally been identified as “craft”, are all processes that incorporate the thoughtfulness, skill, personal involvement and transference that we have come down the centuries to think of as “Art”. This is no less true of a hand-carved colonial gravestone, an Eastlake chair, or a letterpress printed and hand-bound codex than it is of Michelangelo’s David or deKooning’s Montauk Highway. Genuine art has never been limited by the kind of thing a person chooses to make, but by the quality and intensity of the care, attention, emotional investment and intelligence of its maker — for all of which nebulous, even metaphysical contents, the physical object becomes a fixed repository and potential translator in the material world.

It doesn’t matter if these made things are traded for money, given away, or simply left in an attic or warehouse to be forgotten and perhaps discovered later. The exact manner or value of the trade that conveys them from maker to whatever owner or place in which they land, is completely distinct from the objects themselves, which will outlive all such fleeting transactions until they too pass from the world by way of neglect, outright destruction or a slow deterioration. The genuine value of art is not determined by what it costs, but by the degree to which it is loved and preserved over the long haul by people who have completely forgotten what it cost in the first place. This is why it is such a hopeless project to assign a plausible value to contemporary works; we haven’t figured out yet if they are valuable or not! We still have the once completely unknown Johannes Vermeer’s paintings three and a half centuries on from when they were made, not because they were identified as having exceptional monetary or cultural value at the time (which they were not), but because they were such powerful objects in themselves that all those generations of individuals who found themselves in possession of one thought them worthy of preservation. Only time will tell if the emanations of a Richard Prince, Damien Hirst, or Jenny Holzer will be treated with similar reverence going forward.

Money does not confer real value or quality to the things of art any more than a lack of money denies it. Therefore, deciding arbitrarily that some object is worth tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars only stores that arbitrarily monetized figure in the object for possible later retrieval, gain or loss. In all such high-flying transactions, the object’s real artistic merit (or lack thereof) is obscured by its incarnation as an analog of the poker chip, which is nothing more or less than a symbol of trading and purchasing potential.

“The Art World” is a misleading name for the network of institutions and retail outlets that collectively comprise a thriving multi-billion dollar industry in art-like commodities, some of which are genuine works of art, and a great many more of which are relatively shallow imitations of such things. The whole circus is enabled by the enormous volumes of personal capital that have been extracted from our economy, especially in Britain and The United States, over the past forty years since the deregulatory, greed-adoring Thatcher and Reagan eras. All that money has gone into the hands of a vanishingly small minority of players — people who have more cash than any individual could rationally need or use, and who must therefore invent things to do with it, and places to put it, which reinforce the grotesquely egotistical notion that having gotten hold of it in the first place was either a meaningful or an admirable human achievement (without which justification, they might run the risk of actually looking in the mirror).

So where does that leave real art? In the past half century of its hyper-inflation, the contemporary art market has arrogated to itself the authority to pronounce a desired value for the assets it sells, based entirely on nebulous cycles of taste and fashion of which it is itself the principal author. The perverse paradox at the heart of this activity are the conjoined ideas that anything CAN be a “great” work of art, but that only a tiny handful of self-proclaimed experts are equipped to tell us which ones ARE. This hokus-pokus of pretended expertise cannily circumnavigates the deeper truth that real artistic quality is discernable to anybody sensitive and educated enough to be interested in looking for it on their own. This is not to say that art is not a complicated topic, or one that does not genuinely require expertise to understand. The best artists are the masters of skills, both manual and perceptive, that are extremely hard-won and which it takes a substantial amount of education and exposure to successfully deduce. That kind of understanding is what we used to call connoisseurship. It takes work to know this fine stuff when we see it, just as it takes work to learn how to make it. But all of that expertise is available to anybody who is willing to take the time to learn it. Relinquishing it to some expensively hired interpreter is both a forfeit of the pleasure of direct knowledge, and an open invitation to be swindled.

The relationship of money to art is neither as mystical nor as moral as we alternately crass and puritanical Americans want it to be. Artists deserve to be paid, and paid well, for real skill when they have successfully accumulated it — no less so than good doctors, lawyers or chefs are entitled to a rewarding fee in exchange for giving us something we need or desire and cannot make for ourselves. The relative comfort or security of the livelihood that a skilled professional can command is entirely justified by the hard work it took to become that skilled in the first place. But celebrity status and fortunes that are inflated beyond such a rational level soon become ridiculous parodies of the original acts that gave them birth, and inevitably undermine the real quality of the essential one-to-one exchange between maker and viewer that rests at the heart of this curious vocation. If the prices an artist is paid for her or his hard work become fraudulently inflated, that artist (or athlete or rock star) is somehow tainted with that fraud by accepting it, whether they want to admit it or not. This may not impact the quality of the first works sold at such a scale, but if one goes on manufacturing things in pursuit of ever more inflated remuneration and recognition, that hungry motive has a way of creeping into and diminishing the work. If the price I get for a canvas as a life-long and relatively skilled painter is sufficient to keep a roof over my head, support my family and give me more money to paint on, then I have been paid well. If my reputation as a good, or even a great painter grows to the point where I don’t have to work as hard at selling my things as I do at making them, that too feels entirely fair and balanced. But, if I am getting enough money for a single painting to bankroll 20 other painters like myself at that originally rational scale for many decades into the future, well . . . something is out of whack. This is not a point of moralizing so much as it goes to the central critical issue of our age, which is the ideal of sustainability — or of being content with enough, rather than craving too much.

The fact is that we are living in an age of unprecedented excess: excess extraction of our precious resources; excess damage to the ecosystem on which we depend for survival; and above all, excess numbers of human beings overcrowding and using up the fragile world of which we are an embedded part. The whole project of human survival into the future (if it is possible at all) will depend on retreating from such excesses and finding a more sustainable scale at which to live and be human. Art is, as it has always been, a mirror of our realities. At the moment it happens to be reflecting all these fatal excesses. The now numerous documentary exposés which chronicle the corruption of the art market, such as The Price of Everything, Netflix’Blurred Lines, or the late Robert Hughes’s much earlier The Mona Lisa Curse are entertaining, and can outrage and titillate the audience with gusto. But none seems to offer an alternative. They all appear to be saying “This is how it is folks! Get used to it!” And with the exception of Hughes’ film, they also clearly delight in the excess they are reporting, and covertly praise it in a sort of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous fetishism of this preposterous wealth.

This artistic incarnation of human excess has rendered a lot of what was once manageable almost impossible to sustain. There isn’t much we can do, until the bubble bursts, about the way in which the long historical legacies of art that are the province of the great museums have been pushed out of their reach by being too monetarily valuable to acquire or insure. But in terms of contemporary art — art being made now — there has always been an easy antidote to the dilemma portrayed in all those damning documentaries: we just have to stop being enthralled by that giant glowing head within the art world’s lavishly decorated proscenium and take a look behind the curtain at the real wizard of this overblown, technicolor Oz. The reality is that the gorged art market, alongside its supporting network of galleries, auction houses and museums is as tiny and cloistered a realm as the population of absurdly rich patrons who enable the whole intertwined and conflicted network of interests to exist. There are, in fact, legions of artists and makers working outside that universe, who never get any sort of “traction” within it, but who are making things as good as, and often infinitely better than, what it has to offer. The most genuine and best art today is additionally being made, bought and traded at a far more rational economic scale (meaning a scale at which the maker is able to achieve a reasonable livelihood while the buyer is able to attain a very fine thing without bankrupting him or herself) completely outside the precincts of the high-end art market.

In other words: If you are an artist and want to have some success, don’t be discouraged by the awful art world. Ignore it altogether. Instead, put everything you’ve got into learning how to make things that are incredibly hard to make, which make you feel good, and which excite somebody else who you can relate to, to the degree that they are willing to pay you a fair fee to own them. If, on the other hand, you are a sincere lover of art and despair at the corruption or financial obstacles of the market — quit looking for it there. The good stuff is out here in the real world, and easy enough to see if you simply train your own eye and trust it to see the things that matter to you.